Chicken George

A Biography of Documentary Silence

By Steven J. Boardman

Prologue: On Names and the Violence of Records

Before anything else, the question of names must be addressed, because under slavery a name was never a neutral fact.

The man remembered as Chicken George appears in different tellings under different names: George Lea, George McDonald, and occasionally simply “George.” These variations are not evidence of confusion so much as evidence of power. Enslaved people did not control how their names were recorded, altered, inherited, or erased. Surnames were imposed by enslavers, changed through sale, discarded after emancipation, or reconstructed later through family memory.

The name George Lea is used here deliberately. It is the name recorded in the only confirmed federal census entry for the man in 1880 . It is the name used on his grave marker in Bethlehem Cemetery in Henning, Tennessee . It is the name under which his descendants remembered him and claimed him. Whatever other names may have been used during his enslavement, George Lea is the name that survived him.

Claims that Chicken George’s “real” name was George McDonald originate not in archival documentation, but in later genealogical speculation and unsourced repetition. No contemporaneous census, probate, plantation, or church record has been produced linking Chicken George to that surname. In the absence of documentary corroboration, George McDonald remains an attribution without evidentiary standing.

This biography therefore proceeds under the name George Lea, not because it is perfectly proven, but because it is the name that exists where the archive briefly permits him to exist at all.

Part I: The Archive’s Verdict

George Lea was born around 1806. That date is an estimate, inferred from a single census entry recorded when he was already an old man . It places his birth three years after the Louisiana Purchase doubled the territory available for slavery’s expansion, and one year before Congress prohibited the international slave trade while carefully preserving the domestic slave breeding economy that would define the next half century.

The precise location of his birth remains contested. This is how biographies of the enslaved begin: with approximation, with gaps, with the documentary violence that converts human lives into marginalia inside someone else’s property regime.

Alex Haley claimed George Lea was born in Caswell County, North Carolina, the son of Tom Lea, a plantation owner, and Kizzy, an enslaved woman who was herself the daughter of Kunta Kinte, an African captured aboard the Lord Ligonier in 1767. Haley constructed an unbroken lineage from Africa to America, producing a narrative of resistance and survival that made Roots one of the most culturally significant works of the twentieth century.

Gary B. Mills and Elizabeth Shown Mills dismantled that genealogy with methodical precision . Their 1981 article did not merely challenge Haley’s claims. It invalidated them. Plantation records, wills, and census data cited in Roots do not support the narrative. In several cases, they contradict it outright.

The enslaved man known as Toby, whom Haley identified as Kunta Kinte, appears in Virginia records before the Lord Ligonier arrived. Thomas Jarnigan Lea, identified by Haley as George Lea’s father, left a will that names neither a son called George nor an enslaved woman named Kizzy. The Lea family of Caswell County was extensively documented. The specific “Tom Lea” required by Haley’s story does not appear in the record.

So who was George Lea?

The honest answer is that we do not know him in the way the archive allows us to know white men. His enslavers’ births were recorded. Their marriages documented. Their property inventoried. Their disputes litigated. Their deaths announced. George Lea’s pre–Civil War existence occupies a documentary void. That absence is not accidental. It is the intended outcome of slavery’s recordkeeping system.

Part II: The 1880 Census and the Reality of Freedom

On June 10, 1880, a census enumerator recorded George Lea in the household of William P. Posey in Lauderdale County, Tennessee. Age 74. Race: Black. Occupation: servant .

This is the only confirmed federal census record of George Lea after emancipation.

He does not appear with certainty in the 1870 census. If born around 1806, he would have been approximately 64 years old then, five years into freedom, living somewhere in the reconstructed South. The record is silent.

The 1880 entry punctures the triumphant postwar narrative Haley later constructed. Rather than heading a household, George Lea appears as a servant in a white farmer’s home fifteen years after the Thirteenth Amendment. The census does not tell us whether he was paid wages, whether his employment was voluntary, or whether dependency merely replaced bondage in a new legal form. It is also worth noting that there is no evidence that George Lea was ever a grantee in any deed, reinforcing the 1880 census finding that he was a servant, not a landowner .

The census does record something unexpected. The columns for reading and writing are marked “yes” .

Census literacy designations must be treated cautiously. Enumerators sometimes inferred ability, and some formerly enslaved people acquired literacy late in life through churches, freedmen’s schools, or informal instruction. But any plausible explanation carries the same implication: George Lea did not accept the ignorance slavery attempted to enforce. Whether learned secretly during enslavement or later in freedom, literacy at age 74 signals resistance, not accommodation.

It is a fragment, not a biography. But it is not nothing.

Part III: The Photograph and the Archive’s Gaze

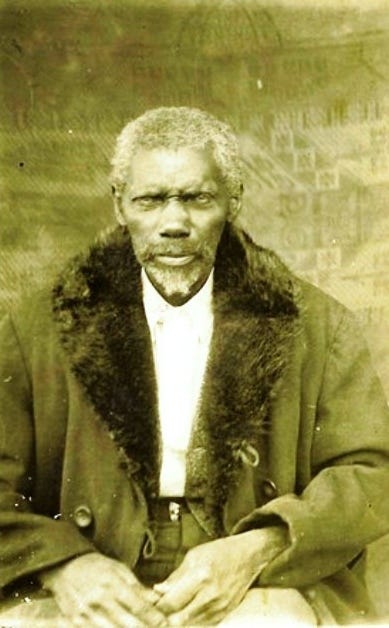

A formal portrait photograph of George Lea exists, held in the collections of the Alex Haley House Museum in Henning, Tennessee, and preserved as a postcard by the Tennessee State Library & Archives . The photograph shows an elderly Black man, seated, wearing a heavy coat with a fur or fleece collar. He has white/gray hair and appears to be in his later years. His hands are folded in his lap, and he gazes directly at the camera with a solemn expression.

The photograph’s provenance is a case study in the complexities of archival evidence. The image was uploaded to Find a Grave in 2012 by a user without any source citation . However, the Tennessee Virtual Archive holds a postcard featuring a photograph of the framed portrait, taken by D. Andrew McNally and funded by the Tennessee Historical Commission . The postcard indicates the original framed portrait is at the Alex Haley Museum.

While the photograph is a powerful artifact, its identification as George Lea relies on family tradition and the museum’s attribution, not on contemporary labeling. The original photographer and date are unknown. If authentic, the portrait was likely taken in the 1880s, consistent with his age in the 1880 census. The formal studio setting suggests that George Lea, a man who appears in the census as a servant, had the means and desire to have a formal portrait made—a significant act of self-representation for a formerly enslaved person.

This photograph, then, is a testament to the power of family memory and the determination to preserve a history that the official record sought to erase. It is a face to a name that the archive otherwise reduces to a single line in a census ledger.

Part IV: The England Story and Why It Cannot Be Literal

Haley’s account places George Lea in England in the 1850s, sent abroad to pay off Tom Lea’s gambling debts. This episode is not merely undocumented. It is structurally impossible.

Thomas Jarnigan Lea died in 1844 or 1845 .

A dead enslaver cannot dispatch an enslaved man across the Atlantic a decade later. No surviving probate record transfers George Lea in such a manner. No shipping records place him abroad. The timeline collapses under basic chronology.

This does not mean no enslaved cockfighters traveled, or that no enslaved men were hired out at great distance. It means this specific episode cannot be treated as literal history. However, such stories often encode real experiences—perhaps George was hired out at great distances, or perhaps the “England” story is a compressed memory of separation and return. The point isn’t to rescue Haley, but to acknowledge that oral traditions often preserve emotional truths even when factual details drift.

Part V: Death, Burial, and the Authority of Descendants

George Lea died in 1890 at approximately 84 years of age. He is buried in Bethlehem Cemetery in Henning, Tennessee. His grave marker identifies him as Chicken George and traces descent from Kunta Kinte .

That marker is not genealogical proof. It is something else entirely.

It is evidence of narrative necessity.

His descendants erected it not because the archive confirmed the story, but because the archive had erased it. Where documentation failed, memory intervened. The stone records not historical certainty, but familial insistence that George Lea was more than “servant, age 74.”

Part VI: Tom Murray and the Point Where the Archive Begins to Cooperate

George Lea’s son, Tom Murray, appears clearly in the documentary record. Born enslaved around 1833, Murray is listed in the 1870 census in Alamance County, North Carolina as a blacksmith with $200 in personal property . Five years after emancipation, that sum represents extraordinary economic positioning.

Blacksmithing was a skilled trade. Enslavers trained men in such crafts for profit. After 1865, that same skill allowed some freedmen limited mobility. Murray migrated to Henning, Tennessee, purchased land in 1886 from D.M. Henning, and established a permanent blacksmith shop . The National Register of Historic Places nomination for the Alex Haley House and Museum State Historic Site notes that Tom Murray mounted his blacksmith shop on wheels to “circumvent a local prohibition against Negro-owned businesses,” a powerful testament to his ingenuity and determination in the face of Jim Crow .

From this point forward, biography becomes possible. Deeds exist. Churches appear. Marriages are recorded. The archive opens because freedom, however constrained, allows documentation.

George Lea never received that benefit.

Conclusion: Biography as Resistance

George Lea’s life survives in fragments: a birth estimate, a census line, a grave marker, a photograph, and the achievements of his descendants. The archive preserves his enslavers in exhaustive detail while reducing him to absence. This was not a failure of recordkeeping. It was its purpose.

Alex Haley filled that silence with mythology. The Mills dismantled that mythology with evidence. Both were responding to the same crime: the systematic destruction of enslaved people’s biographies.

George Lea deserved more than “servant, age 74.” He deserved records that acknowledged his humanity. Slavery denied him those records. His descendants refused to accept that denial as final.

This is his biography, not because it is complete, but because completion itself was the privilege withheld from him.

That is the truth the archive cannot tell.